What are cacti and succulents?

Cacti and succulents are some of the most popular and charismatic plants appearing in private collections the world over—perhaps even as part of your own. Their unexpectedly beautiful blooms and unusual, characterful shapes and textures have made them a firm horticultural favourite.

What exactly are succulents and cacti?

Succulents are found across the globe in nearly all types of habitat, but most often in arid or semi-arid parts of the world. They’re specially adapted to deal with dry, desert-like conditions, and able to store water in one or more of their organs; their leaves, stems, or roots are often filled with water-storing tissue, and are thus unusually fleshy and enlarged. Succulent families include aloe, agave, and, most famously, cacti (the Cactaceae family). While most all cacti are succulents, not all succulents are cacti; cacti are distinct because of the small round nodules seen speckled across the plant (known as areoles) from which they grow and produce flowers and spines.

What makes them vulnerable?

Our love for cacti has its downsides. These plants are suffering because of their horticultural desirability, which has led to them being illegally collected and traded internationally. Aesthetic appeal aside, many cultures enjoy these spiky species for their economic, societal, and ecological significance worldwide; they are used as sources of food for humans and animals, for shelter and construction materials, and in the production of traditional medicines, drugs, oils, and cosmetics.

Additionally, the parts of the world that host succulents are also facing a high risk of destruction—these areas are some of the first to feel the effects of urban expansion, land-use change for agriculture, building of new infrastructure, mining, grassing, and many other human-induced changes. This destroys the natural habitat for succulent species, many of which live in very small and specialised regions and are thus particularly vulnerable.

Why cacti need our help

To assist the global conservation of cacti and succulents, the CSSG made one of its primary goals to assist with evaluating all cactus and succulent species according to the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria.

The IUCN’s Red List is the world’s most comprehensive source of information about the extinction risk of species. This resource uses the best and most up-to-date scientific data available. It contains details of a species’ extinction risk and information on current and anticipated threats, ecology, habitat requirements, use, trade, any past, present, or future conservation efforts.

One of the CSSG’s primary goals was to evaluate the vulnerability and extinction risk of all known cactus species according to the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria—this highly collaborative project was called the Global Cactus Assessment. We completed this goal in 2015, producing the first global species assessment for the largest plant group ever evaluated.

More than 60 cacti experts worldwide participated in nine workshops, reviewing information on the species distribution maps, population size and trend, habitat, conservation actions in place and needed, and threats.

Our assessment revealed cacti to be one of the most threatened taxonomic groups assessed to date: almost a third (31%) of the 1,478 species evaluated are classified as threatened.

Threats faced by cacti

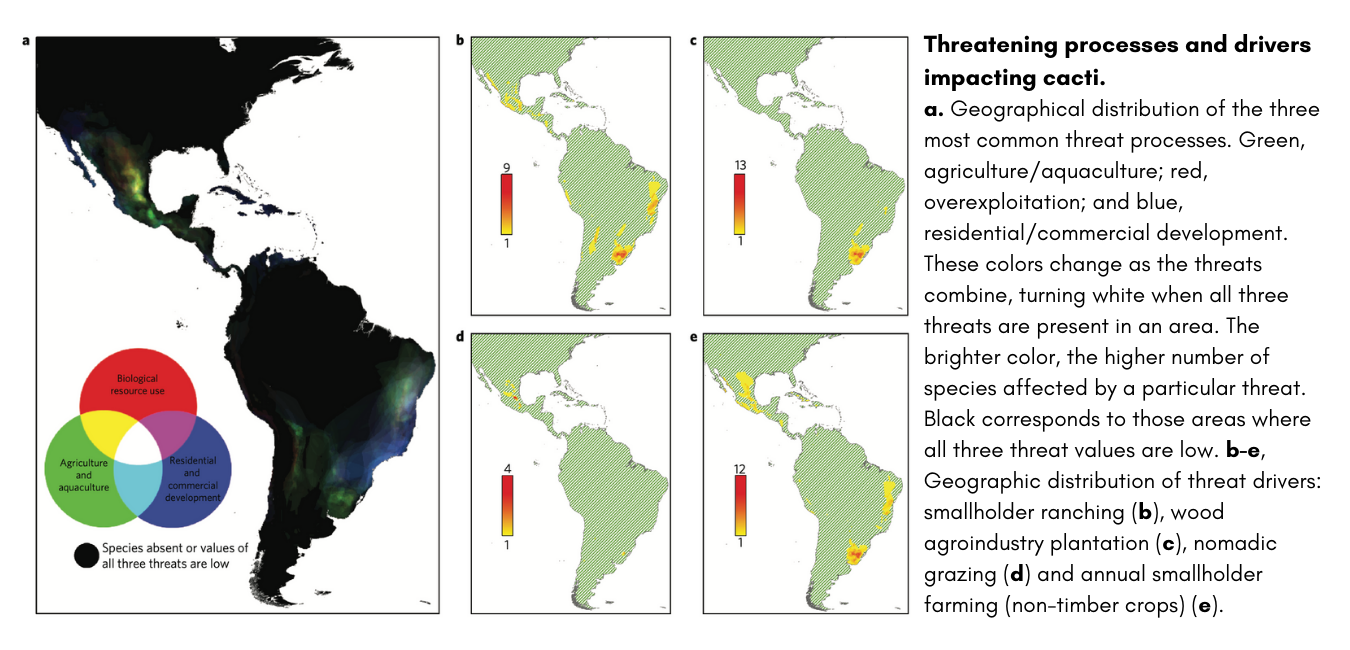

Cacti face significant pressure from anthropogenic sources in arid lands—land conversion to agri- and aquaculture, collection as biological resources, residential and commercial development, smallholder livestock ranching, and smallholder annual agriculture. Horticultural pressures drive these threats; cacti are especially affected by humans unsustainably collecting and often illegally trading seeds and live plants for private ornamental collections—some 86% of threatened cacti (203 cactus species) used for horticultural purposes (including private collections) are extracted from wild populations.

Such trading has been reduced to a certain extent by including the whole cacti family in CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), which works on a global scale to protect endangered species that are traded internationally, in 1975. However, this threat is still of significant concern, especially in countries where CITES has only recently been enforced (Peru, for example, which also happens to be an area where cacti are greatly at risk).

The regions in which cacti are most threatened (‘hotspots’) tend not to overlap much with hotspots for other groups: while cacti predominantly live in arid areas, other threatened species (mammals, amphibians, birds) exist largely in more mesic (moist) areas. Threatened cacti hotspots are found across the Americas—Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, Chile—alongside many areas that contain high numbers of threatened species, but slightly lower species richness—Guatemala, Colombia, and Peru—and centres of cactus diversity—the Chihuahuan Desert and Tehuacan-Cuicatlan regions of Mexico, southern Bolivia, eastern Brazil.

Assessing all plant species: an achievable goal

Determining all known plant species' threat status has been identified as a key target for the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011-2020 (following on from the failure to meet this goal as of 2010), but progress remains slow.

However, our assessment suggests that global species assessments should be readily achievable for major plant groups with moderate resources; we estimate that our assessment process took roughly six hours and US$167 per taxon, including paid staff time, volunteered expert and staff time, and workshop costs. In a year, one full-time member of staff coordinating all aspects of a global assessment could evaluate around 363 species and at a lower cost than many standard research grants issued through major funding bodies. To assess all plant species by 2020, it would take at least 157 people working full-time for five years. It would cost approximately US$47 million—an achievable amount and crucial to the survival of plant species the world over.

What can be done?

For more information on our action plan, read more here.

CITES species

CITES: the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Adapted from: McGough, H.N. Groves, M. Sajeva, M. Mustard, M.J. & Brodie, C. (in press). CITES and Succulents: a User's Guide.

Why Protect Succulent Plants?

International demand for plants can threaten wild populations through over-collection. As a result, many succulent plants are listed on CITES. The Convention aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants' specimens does not threaten their survival.

Like other plant groups, the survival of many wild populations of succulent plants is threatened by a wide range of human activities. Succulent plants are of particular interest to the horticulture industry, being naturally desirable to consumers because of their unusual growth forms and characteristics. However, succulent plants are not only an essential commodity to the multi-million dollar horticulture industry. They are also used for food, fodder, fibres, shelter, and important medicines, drugs, oils, and cosmetics.

‘New’ uses are constantly being found for succulent plants, often based on traditional use. The San Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert break off and suck fragments of the succulent Hoodia gordonii (Asclepiadaceae, not listed on CITES) to suppress hunger cravings while on long hunting trips. A drugs company is now investigating the plant to develop an appetite suppressant drug for the growing obesity market. Negotiations have been carried out between the patent holders and the San elders to secure a benefit-sharing agreement to allow access to profits from a drug market, potentially worth 100’s of millions of dollars.

Global Trade

Succulent plants are traded in large volumes for the horticultural market. By far, the majority of these plants are artificially propagated. These plants' sources range from small local nurseries within range states to large industrial-scale operations outside the range countries. Large scale production in the past centred in the industrialised north, with Europe, the USA, Canada and Japan being the prime centres of production. However, over the last decade, several other countries have become significant players in global trade. For example, the Dominican Republic is now a significant exporter of succulent plant taxa. Within Asia, China and the Republic of Korea are expanding their plant-propagation programmes. Within Africa, South Africa remains the major centre for specialist nurseries propagating native plants. South Africa also cultivates, to a lesser degree, succulents from Madagascar and other African states.

What Groups Are Controlled?

There are four major succulent plant groups covered by CITES - the cactus family (Cactaceae), the succulent Euphorbia species (Euphorbiaceae), the genera Aloe (Liliaceae) and Pachypodium (Apocynaceae). The Cactaceae is by far the largest and best-known group and includes over 2,000 species. There are over 700 succulent species from 2,000 species in the genus Euphorbia, over 400 species in the genus Aloe and 14 species in the genus Pachypodium listed in the Appendices. If you include cacti, there are well over 3,000 species of succulent plants covered by CITES.

The minor succulents listed on CITES are the species Nolina interrata (Agavaceae), Lewisia serrata (Portulacaceae), three species of Agave (Agavaceae), all species of the Didieraceae family, three species in the genus Fouquieria (Fouquieriaceae), two species of the genus Dudleya (Crassulaceae), and all species in the genera Anacampseros (Portulacaceae) and Avonia (Portulacaceae).

Cacti

The Cactaceae is a large and important family of succulent plants. Species range from the minute dwarf cacti hidden in the sands and gravel of the desert to the giant Saguaro cacti (Carnegiea gigantea) - the well-known backdrop to every cowboy movie. Virtually every North American and European home has had a cactus plant on its kitchen window sill - most likely a brightly flowered cultivar of Schlumbergera, the Christmas Cactus. The first reports of cacti cultivation in Europe date back to the 1500s, following their introduction from the Americas. Today, Europe produces millions of propagated cacti per year from its horticultural industry. However, there remains a persistent demand for species collected from the wild.

The entire Cactus family is included in CITES Appendix II, with a number of the most endangered species listed in Appendix I. Cacti are endemic to the Americas except for just one genus, Rhipsalis, whose distribution stretches from South America to southern Africa and Sri Lanka. The Cactaceae family is characterised by stems that bear specialised felted discs called areoles from which develop spines, an exclusive feature of this plant group. The ‘hot spot’ for species diversity is Mexico and the adjacent south-western USA, where nearly 30% of cacti genera are endemic, and nearly 600 species are native. Brazil, northern Argentina, Bolivia, Peru and Chile are important secondary centres of diversity.

In addition to increasing habitat destruction, illegal collection for international trade continues to be a threat, with new threats emerging all the time. For example, the demand for desert plants for landscaping has fuelled the consumer market in succulent plants. TRAFFIC North America estimates that between 1998 and June 2001, nearly 100,000 succulents, with an estimated value of US$3 million, were harvested from Texas and Mexico to supply the landscape garden market in Phoenix and Tucson.

Succulent Euphorbia

The genus Euphorbia includes over 2,000 species, with representatives distributed throughout the world. Their habit ranges from annual plants and shrubs to large trees and succulent species. The best-known plant in the genus is E. pulcherrima or Poinsettia, which is not CITES controlled!

Most euphorbias have green, succulent stems and range in size from only a few centimetres tall (E. obesa) to over 4 metres tall (E. persistentifolia). Leaves are usually reduced in size and ephemeral, and spines are often present at the stems' edges. In very simple terms, succulent Euphorbia have three life forms - tree-like, shrubby, and root or ‘caudiciform’ succulents. The succulent Euphorbia take the same role in Africa as the cacti do in the Americas. All succulent species of Euphorbia, of which there are about 700, are listed in CITES Appendix II. Also, ten dwarf succulent Madagascan species are listed in CITES Appendix I.

How do you know which Euphorbia species are succulent and therefore controlled by CITES? The CITES Conference of the Parties has adopted a specially commissioned checklist covering these species. The CITES Checklist of Succulent Euphorbia Taxa outlines the succulent Euphorbia described and accepted by CITES. However, succulent Euphorbia described since 2003 are still controlled even though they are not on the checklist. Contact your national CITES Scientific Authority or the CITES Secretariat for information on the recently described species.

Euphorbia Trade

The vast majority of recorded CITES trade in succulent Euphorbia taxa is in live plants for the horticultural industry. This trade is mostly in artificially propagated plants. The Dominican Republic, Haiti, Denmark, Thailand and South Africa are all major sources of propagated material.

South Africa and Madagascar are the main suppliers of wild plants to the horticultural industry and specialist collector. The CITES trade data show a large variety of wild-collected succulent Euphorbia taxa in trade, with the majority being exported to western Europe, Japan and the USA.

The major importers of succulent Euphorbia species between 1997 and 2001 were the USA, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, China, Canada and Japan. All of these countries imported more than 10,000 live plants between 1997 and 2001. However, the greatest importer of succulent Euphorbia taxa is the United States of America and the two largest exporters, the Dominican Republic and Haiti, almost exclusively supply this market.

Aloe

There are over 500 taxa in the genus Aloe, concentrated in southern and eastern Africa and Madagascar. Twenty-two Aloe species are listed in CITES Appendix I. The remainder of the genus, excluding Aloe vera, is listed in CITES Appendix II.

Aloe species can be identified by their characteristic leaf structure. However, their life form varies considerably! Species range from the 20-metre tall “tree aloes’’ to miniature plants that are only a few centimetres high. Although the different species can be pretty contrasting, their leaves are usually very similar.

Although Aloe species are generally recognised by their rosettes of succulent leaves and tall, candle-like inflorescences, these characteristics are also features of several other succulent genera, such as Agave (see below how to distinguish an Aloe from an Agave). The juices contained within the leaves of some species of Aloe have been used for medicinal and cosmetic purposes for centuries. Aloe vera, the only Aloe species not covered by the CITES Convention, is propagated worldwide to supply the medicinal and cosmetics industries.

Aloe or Agave?

Aloe species may closely resemble Agave species. Both genera possess species with rosettes of succulent leaves and flowers produced at the end of long flower spikes. For plants in trade, it is best to use the leaf characteristics to distinguish between Aloe and Agave plants.

If the leaves are soft, juicy, and snap cleanly in two, it is likely to be the Aloe leaf. Aloes are soft succulents. In contrast, Agave species are leathery, or hard succulents as their hard and fibrous leaves do not snap cleanly in two. Also, Agave leaves tend to have a stout spine on the end of their leaves. The number of spines on the leaves is less useful as a distinguishing characteristic as it is quite variable in both genera. Aloe spines are soft and easily broken, whereas Agave spines are stout, coarse and very sharp! Another useful way to distinguish an Aloe from an Agave is to look at how new leaves emerge from the plant. New Agave leaves peel off, one by one, from a central leaf cone, often leaving a perfect impression or outline of a leaf on this central cone. In contrast, new Aloe leaves appear singly and are not connected to a central cone.

The structure of the flower spike of an Aloe is relatively easy to tell apart from that of an Agave. Aloe flower spikes rarely reach over 1.5 metres tall. In contrast, Agave flower spikes may reach several metres in height.

Aloe Trade

Next we will name the major importing and exporting countries of Aloe plants, parts and derivatives between the years 1997-2001.

The trade in Aloeis dominated by two markets - the cosmetic/medicinal industry and horticulture. South Africa is the major exporter of Aloe plants, parts and derivatives. As well as artificially propagated plants, South Africa exports significant quantities of wild plants, mainly wild Aloe ferox for the cosmetic/medicinal industry. South Africa has also exported a range of other wild Aloe taxa, in much smaller quantities, for the horticultural market.

South Africa almost exclusively supplies the demand for wild Aloe leaf extracts (mainly Aloe ferox) for the markets in North America, Europe and Asia. Virtually all of the recorded trade in wild plant extracts between 1997 and 2001 has been in Aloe ferox from South Africa. Although not a significant exporter of Aloe, Madagascar has also been a source of a range of wild Aloe plants for the horticultural trade.

Canada, the Republic of Korea and Spain have exported the largest quantities of artificially propagated plants. The major markets for live plants are the United States of America, China and Switzerland.

Pachypodium

Thirty taxa of Pachypodium are accepted in the CITES standard reference for these genera, the Aloe and Pachypodium Checklist (Eggli et al., 2001). These species show remarkable variation in growth form.

- Pachypodium geayi

- is a tree-like stem succulent

- P. namaquanum

- has a branching shrubby growth form when older

- P. brevicaule

- resembles a pile of rocks;

- P. bispinosum

- has its water storage organ below ground.

These growth forms are in great demand from the specialist collector. The genus Pachypodium is listed in CITES Appendix II, and three species are listed in CITES Appendix I. The Appendix I species are all Malagasy species and were listed in the 1990s due to their rarity and trade demand.

Global Distribution of Pachypodium

Pachypodium is a genus with a highly restricted distribution. Twenty-three of the 30 accepted Pachypodium taxa listed in the CITES Aloe and Pachypodium checklist are only found in Madagascar. Of the remaining seven taxa included in the checklist, six are located in southern Africa, and one is only known in cultivation.

Pachypodium Trade

The recorded international trade in Pachypodium is virtually confined to live plants for the horticultural market. The United States of America is by far the largest exporter of these, shipping large quantities of artificially propagated plants to markets worldwide. Canada is the major importer of Pachypodium; most of its plants originate from the USA.

Most wild Pachypodium taxa in trade originate in Madagascar. European countries (Germany, Norway, Switzerland and Italy) are the primary market for these plants.

Other Succulent Taxa Listed on CITES - Agave, Didieraceae and Fouquieria

Although there are over 200 species in the genus Agave, only three species are regulated under CITES, not including the species used to make tequila! Agave arizonica and A. parviflora are listed in Appendix I, while A. victoria-reginae is in Appendix II. Be aware that A. parviflora can look exactly the same as the non-listed A. polianthiflora when not flowering! All of the controlled species occur naturally in the USA or Mexico. There is unlikely to be any problem with international trade in these species.

The Didiereaceae is a small family of succulents made up of four genera, Alluaudia, Alluaudiopsis, Decarya and Didierea. Many taxa have an erect column-like habit similar to columnar Euphorbia or cacti. They are an essential part of the dry thorny forest of southern and south-western Madagascar. They are threatened by habitat clearance, burning and charcoal production. Demand for wild plants of these taxa for the specialist horticulture trade peaked in the 1980s before propagation became more common.

There are three species in the genus Fouquieria (Fouquieriaceae) listed on the CITES appendices - F. fasciculata and F. purpusii are listed in Appendix I while F. columnaris is included in Appendix II. The genus comprises some 11 species and is confined to Mexico and the Southwest of the USA. In the case of F. columnaris (Boojum tree), it can form dramatic columnar trees up to 18 metres tall and 400 years old. Fouquieria purpusii and F. fasciculata are smaller shrubs native to Mexico and attractive to the collector. International trade in wild plants outside North America is unlikely.

Other Succulent Taxa Listed on CITES

Anacampseros and Avonia (formerly included in Anacampseros).

There are over 20 species in this group, the majority found in Africa. The African species are of horticultural interest, with specialist collection being a potential threat. However, the current CITES trade data suggests only very low levels of trade. However, there have been reports of illegal trade in Anacampseros alstonii in eastern Europe.

Welwitschia mirabilis

This is a unique, long-lived (up to 1,500 years) succulent plant that survives on moisture from fog and dew. It was formerly listed in CITES Appendix I. Still, it was later downlisted to Appendix II as the plant is relatively common within its habitat and is well protected in its native range. It is native to Angola and Namibia and is not likely to be traded from the wild, with the possible exception of seeds. Welwitschia mirabilis is the only species in this genus.

Dioscorea deltoidea

This species is listed in CITES as it is traded for its medicinal properties, and we will discuss it under that section.

Nolina interrata

It is listed in Appendix I since 1983. Nolina interrata, or Dehasa Beargrass, is a native of southern California, USA. It is restricted to a few localities in San Diego County and also Baja California, Mexico. It is a grass-like succulent with a flattened swollen base. International trade in wild plants is unlikely.

Lewisia serrata

It is a small perennial of some interest to alpine plant enthusiasts. It is confined to the shady, mossy cliffs of the rivers that drain the Sierra Nevada in eastern California, USA. This species is available as propagated plants in more than sufficient numbers to supply the trade demand. International trade in wild plants is unlikely.

Dudleya stolonifera and Dudleya traskiae

These are two rare species endemic to California, USA. International trade in wild plants is unlikely.

Medicinals

CITES controls and monitors the trade in several succulent plants, which are important as medicinals. There are twelve species of Aloe (excluding Aloe vera, which is no longer CITES controlled), eight species of Euphorbia, and Dioscorea deltoidea recorded as having medicinal uses.

Of the CITES controlled succulents, the most important medicinal plants are Aloe ferox and Dioscorea deltoidea. Native to South Africa and Lesotho, Aloe ferox is used to produce aloe bitters and gels. The leaves are collected to make the bitters used in drinks and medicines and for gels and creams used in skin and hair care products. Aloe bitters are used traditionally as a laxative or purgative, to combat arthritis, and in veterinary medicine. Aloe-Emodin is reported to have anti-cancer activity in vitro. South Africa is the major exporter, and the trade occurs as extract, powders and leaves. A report of the Aloe ferox trade by Newton and Vaughan (1996) estimate that the leaves of approximately 17 million plants are harvested annually to produce some 400 tonnes of Aloe bitters. This trade is considered to be sustainable, as only the leaves are harvested, the plant is relatively common, and a large section of the wild population is never subject to harvesting.

Dioscorea deltoidea occurs in Asia, mainly in the Himalayas and Indochina. It has been traditionally used as an anti-rheumatic, and in western medicine, the tubers have been used as a steroid drug source. Diosgenin, present in the tubers, is the basis of cortisones, sex-hormones and anti-fertility drugs, including the contraceptive pill. The production of these drugs has now moved to use synthetic products with limited extraction from plants. International trade in the raw material is now likely to be limited to the Himalayan region. Although there are reports of trade between Nepal and India, there are no official statistics, and no CITES trade recorded in the UNEP-WCMC statistics since its listing in 1975.

Implementing CITES for Succulent Plants

The enforcement of CITES controls is carried out at different levels. Within an exporting country, it is carried out by the inspection of nurseries, traders, markets, and, less frequently, most importantly, of the plants at the time of export. Inspections can also occur at the time of import and post-importation in the major trading countries. Enforcement agencies also survey trade shows, advertisements in the trade press and the World Wide Web.

Few countries have enforcement teams specially trained to identify CITES specimens - animals or plants. CITES enforcement for plants is most likely to be carried out by general Customs staff or officials trained in plant health controls. When CITES enforcement is carried out by general Customs staff, the enforcement procedures are concentrated on the documentation - not the plants. Thus, Customs may check to see if the permits are correctly filled in, stamped and issued by the correct authorities. They also check other documents and invoices to see if any CITES material named on the accompanying documentation is missing from the CITES permits.

Where such general Customs staff are used to check CITES plants, is it vital that they have contact with a centre of expertise on identifying and conserving plants. Such a centre should be the national Scientific Authority. However, in some cases, the national Scientific Authority may be a committee or a government department with expertise centred on animals. In this case, the enforcement authorities should build a relationship with a national or local botanic garden or herbarium. Such a relationship is vital.

The Customs Officers will need some basic training on the plants and parts and derivatives covered by CITES and will need help targeting detrimental trade. Most importantly, Customs officials will need access to experts who can identify CITES plants. Such experts can also advise on and have access to facilities for holding seized or confiscated material. These scientists may be called on to be expert witnesses, which are vital if breaches of the controls result in prosecution and court appearances.

Enforcement - Checks

Documents - Check the CITES permits' authenticity (signatures, stamps), and check the plant names and number of specimens on the permit against the delivery note or invoice. Also, check the source of the plants - are they declared as wild or artificially propagated?

Country of origin – Always check the country of origin on the permits. Are the succulents being exported from a country where the plants grow in the wild? If so, then the plants may be more likely to be wild collected. Most countries have banned the export of wild-collected plants. Countries may express concern over the illegal export of their wild collected succulent plants and ask for the assistance of other CITES parties and non-Parties to control this trade. Usually, such a request is published as a Notification to the CITES Parties (you can find this on the CITES website: www.cites.org).

Packaging - Nurseries will usually wrap and package their plants carefully to avoid damaging them. They are then shipped in boxes marked with the nursery’s name and with printed labels. Consignments of illegally collected plants may be poorly wrapped using local materials, contain handwritten labels (sometimes with collecting data), and the plants may not be identified to species level to disguise the fact that new unnamed species may have been collected.

Consignments of plants - Collections of illegal plants usually consist of small samples of plants of different size and age groups that are not uniform in shape. They may be damaged (broken or snapped roots), and soil and weeds or native plants may be present amongst the stems and roots. Artificially propagated plants will be uniform in size and shape and be clean of soil, pests and diseases, weeds or native plants.

Trade routes & smuggling - Illegal collections of rare or new species may be shipped using the postal / courier services or hand luggage to avoid detection. Collections may also be split up and sent in several different packages to ensure both a high level of survival and that some of the plants will evade being discovered.

Exemptions

When plants are listed in the CITES Appendices, the listing may be annotated. The annotation aims to target the listing of the plants and the parts and derivatives which are likely to be traded from the wild and which can also be identified. Certain species or parts of plants may be exempted from a listing. Generally, no annotations apply to Appendix I listings; in that case, all of the plant and its parts and its ‘readily recognisable’ derivatives are controlled. No special exemptions apply to the succulent plants presently listed on Appendix I of the Convention.

Two Appendix II taxa, Dudleya stolonifera and D. traskiae, have no annotation. Just the live and dead plants are controlled, and no parts or derivatives are subject to control. In the remainder of the succulent plants in Appendix II, the standard annotation #1 applies. This annotation excludes from CITES control seeds, spores (including pollinia), tissue cultures and cut flowers from artificially propagated plants.

In addition, two special exemptions apply to succulent plants. Aloe vera is excluded from the generic Aloe listing because the species is only known in cultivation and as a naturalised plant. It has been so long in cultivation that its exact natural distribution and origin is unknown. Artificially propagated specimens of cultivars of Euphorbia trigona are excluded from the Euphorbia listing because they are propagated in huge numbers and bear no threat or indeed resemblance to the wild plants.

The CITES Nursery Registration System

The CITES procedures for nursery registration are laid down in Resolution Conf. 9.19 Guidelines for the registration of nurseries exporting artificially propagated specimens of Appendix I species. This was adopted at the 9th Meeting of the Parties' CITES Conference in Fort Lauderdale, USA, in November 1994. CITES has not laid down any criteria for the registration of nurseries that propagate Appendix II plants. However, any national CITES authority is free to set up an Appendix II registration scheme with, for example, a fast stream permit system. This would benefit the local authorities and traders; however, the registration would have no recognition outside that country.

The Management Authority (MA) of any Party, in consultation with the Scientific Authority (SA), may submit a nursery for inclusion in the CITES Secretariat’s Appendix I register. The owner of the nursery must first submit to the national MA a profile of the operation. This profile should include, among other things, a description of facilities, propagation history and plans, numbers and type of Appendix I parental stock held and evidence of legal acquisition. The MA, in consultation with the SA, must review this information and judge whether the operation is suitable for registration. During this process, it would be expected for the national authorities to inspect the nursery in some detail.

When the national authorities are satisfied that the nursery is bona fide and suitable for registration, it passes on this opinion and nursery details to the CITES Secretariat. The CITES MA must also outline details of the inspection procedures used to confirm the identity and legal origin of parental stock of the plants to be included in the registration scheme and any other Appendix I material held. The national CITES authorities must also ensure that any wild origin parental stock is not depleted and the overall operation is closely monitored. The CITES MA should also put in place a fast stream permit system and inform the Secretariat of its details.

If satisfied with the information supplied, the CITES Secretariat must then include the nursery in its register of operations. If not satisfied, the Secretariat must make its concerns known to the CITES MA indicate what needs to be clarified. Any CITES MA, or other sources may inform the Secretariat of breaches of the requirements for registration. If these concerns are upheld, then following consultation with the CITES MA, the nursery may be deleted from the register.

CITES Definition of ‘Artificially Propagated'

The CITES definition of artificially propagated is included in Resolution Conf. 11.11- Regulation of trade in plants. The definition within CITES includes several unique criteria. The application of these criteria may result in a plant that bears all the physical characteristics of artificial propagation being considered wild-collected in CITES terms. The key points are:

- Plants must be grown in controlled conditions. For example, this means the plants are manipulated in a non-natural environment to promote prime growing conditions and exclude predators. A traditional nursery or simple greenhouse is ‘controlled conditions’. A managed tropical shade house would also be an example of ‘controlled conditions'. Temporary annexation of a piece of natural vegetation where wild specimens of the plants already occur would not be ‘controlled conditions’. Also, wild-collected plants are considered wild even if they have been cultivated in controlled conditions for some time.

- The cultivated parent stock must have been established in a manner not detrimental to the survival of the species in the wild and managed to ensure long-term maintenance of the cultivated stock.

- The cultivated parental stock must have been established following the provisions of CITES and relevant national laws. This means that the stock must be obtained legally in CITES terms and also in terms of any national laws in the country of origin. For example, a plant may have been illegally collected within a country of origin, then cultivated in a local nursery, and its progeny exported declared as artificially propagated. However, such progeny cannot be considered artificially propagated in CITES terms due to the parent plants' illegal collection.

- Seeds can only be considered artificially propagated if they are taken from plants that themselves fulfil the CITES definition of artificially propagated. The term cultivated parental stock is used to allow some addition of fresh wild-collected plants to the parental stock. It is acknowledged that parental stock may need to be occasionally supplemented from the wild. As long as this is done legally and sustainably, it is allowed.

Applying the CITES definition is a complex mixture of checking legal origin, propagation status and non-detrimental collection. To achieve this, the assessment needs to be carried out in close co-operation between the CITES Management and Scientific Authorities. The implementation of the criteria on day by day basis needs to be tailored to the situation in an individual CITES Party. National CITES authorities should consider producing a checklist to standardise the process and inform the local plant traders.

Detecting Detrimental Trade? - The Burden on Exporting Countries

CITES aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants' specimens does not threaten their survival. Appendix I includes those species’ threatened with extinction which are or may be affected by trade’. Trade in wild specimens of Appendix I taxa for commercial purposes is in effect banned under CITES. Appendix II includes’ all species which, although not necessarily now threatened with extinction, may become so unless trade in specimens of such species is subject to regulation to avoid utilisation incompatible with their survival. Trade is allowed in wild Appendix II species subject to permits being issued.

Before granting an export permit for Appendix II plants, a CITES Management Authority must fulfil Article IV of the Convention. This states that an export permit shall only be granted when, among other things,’ A Scientific Authority of the state of export has advised that such export will not be detrimental to the survival of that species’.

This is, in effect, a statement of sustainability which in CITES is termed a non-detriment finding.

Detrimental Trade - How and Why?

1. Due to a lack of resources

The countries that are richest in succulent plants are poor in resources to help them implement the Convention. When resources are available for CITES implementation, they are more than often targeted at implementing the controls for animals. The plant trade may sometimes go un-monitored, and permits are issued without an informed non-detriment statement being made. The information gathered may also be poor; for example, when permits are granted at a generic level, when the data are analysed, it is impossible to judge the effect of trade at the species level. These problems of implementation are all due to a lack of resources in exporting countries.

2. Due to inadequate implementation of export bans on wild plants

Many CITES Parties have now banned the export of wild Appendix II plants for commercial purposes. They have done this in an attempt to control the trade in their wild plant resources. However, very often, the bans are not complemented by the monitoring and control of propagation and nursery facilities. In such cases, wild plants continue to be traded, merely passing through nurseries, picking up documentation stating that they are ‘artificially propagated’ and entering the international market. Ideally, any long term export ban should be accompanied by a national nursery registration scheme.

3. Through smuggling

Succulent plants are smuggled. Smuggling can occur by a variety of means. For example, large commercial consignments can be misdeclared as non-controlled species. The rarest species can be targeted by specialist collectors and smuggled back as freight or hand luggage. Specialist collectors have been known to fund trips to countries such as Mexico by filling suitcases with rare species and selling them on return to Europe or the USA. Many plants are now smuggled through the postal system, or more recently, the favoured method is to use the extensive range of 24-hour courier systems.

Web Sites

There are a large number of sites of some interest to CITES workers. Many national CITES authorities have their own dedicated websites. The following are key sites, and they will lead you to as many other sites as you have time to spend on the Web.

- CITES Home Page

- Official site of the CITES Secretariat. It includes lists of Parties, Resolutions and other documents.

- European Commission

- Information on the Wildlife Trade Regulations that implement CITES within the European Union.

- UK CITES Website

- Website maintained by the UK CITES authorities to provide information and updates on CITES-related matters as they pertain to the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories.

- IUCN - The World Conservation Union

- The world’s largest professional conservation organisation. IUCN brings together governments, non-governmental organisations, institutions and individuals to help nations make the best use of their natural resources sustainably.

- IUCN Species Survival Commission

- SSC is the IUCN’s foremost source of scientific and technical information for the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of flora and fauna. Specific tasks are carried out on behalf of IUCN, such as monitoring vulnerable species and their populations, the implementation and review of conservation action plans, and the provision of guidelines, advice, and policy recommendations to governments, agencies, and organisations regarding conservation and management of species and their populations.

- UNEP - World Conservation Monitoring Centre

- The UNEP-WCMC provides information services on the conservation and sustainable use of the world’s living resources and assists others in developing information systems. Activities include supporting the CITES Secretariat. Information on international wildlife trade and trade statistics may be requested from the Species Programme of UNEP - WCMC. Now a UN office based in Cambridge, UK, the Centre's work is an integral part of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya.

- TRAFFIC International

- TRAFFIC is a WWF programme, and the IUCN established to monitor the trade in wild plants and animals. The TRAFFIC Network is the world’s most extensive monitoring programme, with offices covering most parts of the world. The Network works closely with the CITES Secretariat.

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin

- Track the major environmental negotiations as they happen. Also extensive archive material and lots of photographs of the meetings.

- IOS - The International Organisation for Succulent Plant Study

- Was established to promote the study of succulent and allied plants and encourage international co-operation amongst those interested in them. The IOS is a Commission of the International Union of Biological Sciences and seeks to achieve its goal through biennial international congresses, working sessions, and Bulletin. It is also a strong advocate of conservation and has an extensive Code of Conduct.

Plant Name Checking

The following websites are useful for checking plant names that are not found in the standard CITES checklists. Sometimes these names may be of newly described species. Suppose this 'new name' has been used to apply for a CITES permit stating the plant is propagated. In that case, the plant should be checked to confirm its identity and ensure it meets the CITES definition of artificial propagation.

- IPNI - The International Plant Names Index

- A database of all seed plants' names and associated basic bibliographical details.

- TROPICOS

- A nomenclature database produced and maintained by the Missouri Botanical Garden.

- EPIC - Plant Information Centre

- Brings together all the digitised information on plants held by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Monocot Checklist

- Comprises an inventory of taxonomically validated Monocotyledon plant names and associated bibliographic details, together with their global distribution.